Patent Law’s Definiteness Requirement Has New Bite

The Supreme Court may have shaken up patent law quite a bit with its recent opinion in the Nautilus v. Biosig case (June 2, 2014).

At issue was patent law’s “definiteness” requirement, which is related to patent boundaries. As I (and others) have argued, uncertainty about patent boundaries (due to vague, broad and ambiguous claim language), and lack of notice as to the bounds of patent rights, is a major problem in patent law.

I will briefly explain patent law’s definiteness requirement, and then how the Supreme Court’s new definiteness standard may prove to be a significant change in patent law. In short – many patent claims – particularly those with vague or ambiguous language – may now be vulnerable to invalidity attacks following the Supreme Court’s new standard.

Patent Claims: Words Describing Inventions

In order to understand “definiteness”, it’s important to start with some patent law basics. Patent law gives the patent holder exclusive rights over inventions – the right to prevent others from making, selling, or using a patented invention. How do we know what inventions are covered by a particular patent? They are described in the patent claims.

Notably, patent claims describe the inventions that they cover using (primarily) words.

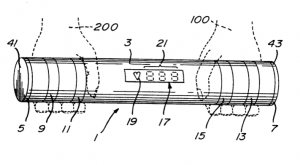

For instance, in the Supreme Court case at issue, the patent holder – Biosig – patented an invention – a heart-rate monitor. Their patent used the following claim language to delineate their invention :

I claim a heart rate monitor for use in association with exercise apparatus comprising…

a live electrode

and a first common electrode mounted on said first half

In spaced relationship with each other…”

So basically, the invention claimed was the kind of heart rate monitor that you might find on a treadmill. The portion of the claim above described one part of the overall invention – two electrodes separated by some amount of space. Presumably the exercising person holds on to these electrodes as she exercises, and the device reads the heart rate.

( Note: only a small part of the patent claim is shown – the actual claim is much longer)

Patent Infringement: Comparing Words to Physical Products

So what is the relationship between the words of a patent claim and patent infringement?

In a typical patent infringement lawsuit, the patent holder alleges that the defendant is making or selling some product or process (here a product) that is covered by the language of a patent claim (the “accused product”). To determine literal patent infringement, we compare the words of the patent claim to the defendant’s product, to see if the defendant’s product corresponds to what is delineated in the plaintiff’s patent claims.

For instance, in this case, Biosig alleged that Nautilus was selling a competing, infringing heart-rate monitor. Literal patent infringement would be determined by comparing the words of Biosig’s patent claim (e.g. “a heart rate monitor with a live electrode…”) to a physical object – the competing heart-rate monitor product that Nautilus was selling (e.g. does Nautilus’ heart rate monitor have a part that can be considered a “live electrode”)?

Literal patent infringement is determined by systematically marching through each element (or described part) in Biosig’s patent claim, and comparing it to Nautilus’s competing product. If Nautilus’ competing product has every one of the “elements” (or parts) listed in Biosig’s patent claim, then Nautilus’s product would literally infringe Biosig’s patent claim.

If patent infringement is found, a patent holder can receive damages or in some cases, use the power of the court to prevent the competitor from selling the product through an injunction.

Patent Claims – A Delicate Balance with Words

Writing patent claims involves a delicate balance. On the one hand, a patent claim must be written in broad enough language that such a patent claim will cover competitors’ future products.

Why? Well, imagine that Biosig had written their patent claim narrowly. This would mean that in place of the broad language actually used (e.g. “electrodes in a spaced relationship”), Biosig had instead described the particular characteristics of the heart-rate monitor product that Biosig sold. For instance, if Biosig’s heart-rate monitor product had two electrodes that were located exactly 4 inches apart, Biosig could have written their patent claim with language saying, “We claim a heart rate monitor with two electrodes exactly 4 inches apart” rather than the general language they actually used, the two electrodes separated by a “spaced relationship”

However, had Biosig written such a narrow patent, it might not be commercially valuable. Competing makers of heart rate monitors such as Nautilus could easily change their products to “invent around” the claim so as not to infringe. A competitor might be able to avoid literally infringing by creating a heart-rate monitor with electrodes that were 8 inches apart. For literal infringement purposes, a device with electrodes 8 inches apart would not literally infringe a patent that claims electrodes “exactly 4 inches apart.”

From a patent holder’s perspective, it is not ideal to write a patent claim too narrowly, because for a patent to be valuable, it has to be broad enough to cover the future products of your competitors in such a way that they can’t easily “invent around” and avoid infringement. A patent claim is only as valuable (trolls aside) as the products or processes that fall under the patent claim words. If you have a patent, but its claims do not cover any actual products or processes in the world because it is written too narrowly, it will not be commercially valuable.

Thus, general or abstract words (like “spaced relationship”) are often beneficial for patent holders, because they are often linguistically flexible enough to cover more variations of competitors’ future products.

Patent Uncertainty – Bad for Competitors (and the Public)

By contrast, general, broad, or abstract claim words are often not good for competitors (or the public generally). Patent claims delineate the boundaries or “metes-and-bounds” of patent legal rights Other firms would like to know where their competitors’ patent rights begin and end. This is so that they can estimate their risk of patent liability, know when to license, and in some cases, make products that avoid infringing their competitors’ patents.

However, when patent claim words are abstract, or highly uncertain, or have multiple plausible interpretations, firms cannot easily determine where their competitor’s patent rights end, and where they have the freedom to operate. This can create a zone of uncertainty around research and development generally in certain areas of invention, perhaps reducing overall inventive activity for the public.

Uncertainty: Do Competitors Have Notice about Patent Boundaries?

This is the problem of inadequate patent notice – notice to the public (and competitors) about the boundaries of patent rights. The more uncertain patent claims are the less notice the public and competitors have about the boundaries of existing patents of others.

For instance, consider the words at issue in Biosig’s patent claims, ““a live electrode and a first common electrode in a spaced relationship .”

Imagine that a competitor like Nautilus wanted to make their own heart-rate monitor that did not infringe Biosig’s patent. Let’s assume that most heart-rate monitors need electrodes in order to detect the heart rate from the exercising person’s skin. In order to not infringe this particular patent, Nautilus would like to make a product in which the electrodes were not in a “spaced relationship.” If they could make such a product in which the electrodes were not in a spaced relationship, they would not be literally infringing Biosig’s patent claim (although they might infringe under the Doctrine of Equivalents).

However, the phrase “spaced relationship” is vague, and has little content on its own. Imagine that Nautilus is reading the patent claim, and is trying to make a product that has electrodes that are not in a “spaced relationship” to avoid infringing Biosig’s patent. How is Nautilus (or any other company) supposed to know what a “spaced relationship” means? How big should the spacing be be? Does it cover all spaces? (Contrast the improved clarity had Biosig claimed “electrodes spaced exactly 4 inches apart”)

The rest of the patent (the specification) might provide some clues as to the meaning, but in general, would be a lot of uncertainty for all competitors, when vague language like this is used in a patent claim. Such uncertainty might deter inventive activity in this area for fear of infringement.

Hence the fundamental problem for society with uncertain and vague patent claim words. If a competitor like Nautilus is to design a heart rate monitor, how are they to know if their product is infringing or not? How can they distinguish one design, in which the are in a spaced relationship (and therefore potentially infringing), from another design, in which the electrodes are not in a spaced relationship (and therefore not literally infringing), if the phrase “space relationship” conveys so little information.

While vague language might benefit the patent holder, it should be clear that such uncertainty creates transaction costs for competitors and society at large. It is difficult for others to tell where patent rights end, and where freed to operate begins. Moreover, such uncertainty allows certain parties to act opportunistically. Patent holders routinely argue that patent claims with vague words should be interpreted to cover products that they were never originally intended to cover. Indeed, this is the very business model behind many patent trolls who often strategically purchase older patents with broad or vague language to extract settlements from companies using different, modern technologies.

The Definiteness Requirement

Enter patent law’s definiteness requirement. Section 112 of the patent act requires a patent applicant to have claims “particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter which the applicant regards as his invention.” This requirement of linguistic specificity has become known as the definiteness requirement. If a patent claim has words that do not meet this standard – they are not definite enough – and the claim should be found invalid.

The Federal Circuit’s Definiteness Standard

You might think by reading the language of Section 112 – the definiteness requirement – that for a patent claim to be valid, the claims must use words if reasonably high precision and specificity. Correspondingly, one might assume that — given that the statute requires that claims “particularly point out” and “distinctly claim” the invention — that vague or general patent claim words would be routinely rejected as not definite enough. However, for many years, this has not been the case.

The reason is that for some time the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals had a very lax interpretation of the definiteness requirement. Prior to the Supreme Court’s Nautilus decision — under the Federal Circuit’s definiteness jurisprudence — patent claim words did not have to be extremely precise or risk failing for lack of definiteness under 112. Rather, the Federal Circuit’s interpretation of “definiteness” seemed to prohibit only words of extreme subjectivity.

According to the Federal Circuit’s standard, a claim would only fail for definiteness if such a claim had language that was “insolubly ambiguous” and “incapable of construction.” Under this standard, even very vague words, without a lot of content, meaning, and notice would pass muster under definiteness. Only words completely incapable of interpretation – insolubly ambiguous – would fail. If there was some way that a court could imagine that a person of skill in the field could conceivably interpret a phrase to have some content, such a word would be considered definite enough — even if that phrase had multiple meanings, or very little inherent content to guide others about the claim’s scope.

Under this standard, extremely vague words passed muster as definite. For instance, courts found that non-specific phrases such as “surrender value protected investment credits” and “anaerobic condition” – even though they provided very little notice about the scope of the patent claim (i.e. What distinguishes an “anaerobic condition” from an “aerobic condition”) – were sufficiently definite to meet Federal Circuit’s lax requirement.

Why were such vague words considered definite? Because the courts found that such words were not “insolubly ambiguous.” Rather, there was some way of interpreting them, even if these phrases were capable of multiple, plausible interpretations, and provided little or no notice to competitors as to what did, or did not, infringe.

Definiteness: Subjectivity Prohibited Under Federal Circuit

Were there any words that were too vague or ambiguous to actually fail the Federal Circuit’s lax definiteness requirement? Yes – albeit a very small subset of claim words: words of pure subjectivity were found to be too indefinite, even for the Federal Circuit’s low definiteness bar.

So, for instance, a patent claim requiring that a process produce a screen that was “aesthetically pleasing” was found to be indefinite. Aesthetic preferences are purely subjective. A competitor would have no way of knowing whether their product was “not aesthetically pleasing” (and therefore not literally infringing), or was “aesthetically pleasing” (and therefore potentially literally infringing). “Aesthetically pleasing” is in the eye of the beholder.

The upshot of the Federal Circuit’s case law was that the definiteness requirement was, for many years, a non-issue. A patent claim could have words that were vague, uncertain and ambiguous, or which had multiple plausible meanings, and which provided very little notice to competitors about what products were and were not infringing. It was very hard to fail the definiteness requirement – patent claim language could still pass the Federal Circuit’s lax standards if it were capable of being resolved somehow according to the court. Thus, few definiteness challenges succeeded.

The Supreme Court’s Definiteness Standard

In the Nautilus v. Biosig case, the Supreme Court has suddenly injected some new life into the definiteness requirement. The Court rejected the Federal Circuit’s lenient, and hard-to-fail “insolubly ambiguous” standard.

What is the Supreme Court’s new definiteness standard? For a patent claim to be definite, it must “inform those skilled in the art [at the time the patent was filed] about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.”

This is a broader, and more subjective standard than the Federal Circuit’s prior “insolubly ambiguous” standard. Under the earlier standard, a patent claim term could be vague and ambiguous, but as long as there was some process to determine its interpretation, then it was sufficiently definite. Under the Supreme Court’s new standard, a claim term is indefinite if it fails to inform a person of skill in the field of invention about the scope of the patent claim.

What does this mean? Well, let’s imagine that in the Biosig case, that “a person skilled in the field of invention” is a mechanical engineer who designs exercise equipment for a living. If such a hypothetical engineer were to read Biosig’s patent claim, and she could not reasonably determine what heart-rate monitor designs the patent claim did (and did not) cover perhaps that claim might be found indefinite and invalid under this new standard.

If that hypothetical engineer, looking at the patent claim with the words “spaced relationship”, and in light of information in other parts of the patent – the drawings and descriptions in the specification and the field of art generally (e.g. might “spaced relationship” have a well-known meaning the field of equipment design) – could not figure out what “spaced relationship” meant within the context of placing heart-rate monitor electrodes, such a claim could be found indefinite, and therefore invalid. However, note that the Supreme Court did not actually find the claims here to be indefinite – they merely remanded it to the Federal Circuit. A finding of invalidity here is not a given, because the new standard gives judges considerable leeway.

Definiteness Standard is Itself Indefinite

Perhaps ironically, the Supreme Court’s new definiteness standard is itself somewhat indefinite. Unlike the Federal Circuit’s earlier lax standard, where largely only words of extreme subjectivity were not definite, and most other things seemed to be definite enough, under the Supreme Court’s new standard, it is harder to know what claim language is and is not definite. This is not necessarily a bad thing, and is in line with the Supreme Court’s pattern of converting Federal Circuit rigid, but more legally certain “rules” into less certain, but more flexible “standards.”

Improving Patent Claim Certainty

On the positive side, this is perhaps one step on the road to patent rules that improve the level of certainty of patent claim scope as compared to those allowed today.

Uncertainty about the scope of patent claim terms has been a persistent problem under recent patent rules. Many patent claims fail to provide notice to the public about what is, and is not covered, by a particular patent claim.

We can acknowledge that language has inherent uncertainties, and that it is impossible (and not necessarily desirable) to make patent claims perfectly certain in scope. Some level of uncertainty in patent claim language is inevitable and even desirable. However, too much uncertainty about patent claims is generally not good for the public.

As I have argued here, just because we cannot make patent claims perfectly certain, does not mean that we cannot adopt procedures and rules that tend to make patent claims incrementally more certain compared to a baseline.

Scope-Clarifying Statements on the Public Record

There are ways of incrementally improving certainty, and there are a number of low-cost interventions that could potentially incrementally improve overall patent certainty compared to today.

For instance, when a patent examiner encounters a very vague word in examining a patent application, she could require a scope-clarifying statement from the patent applicant, on the public patent record.

Our “notice” goal is to inform the public about what is or is not covered by a particular patent claim, so that third-party firms can know with reasonably certainty when their products do or do not infringe.

Thus, when encountering a vague term, like “spaced relationship”, a patent examiner can ask the patent applicant two important scope-clarifying questions: What is X, and What is NOT X . For example, 1) What does it mean for an electrode to be in a “spaced relationship”? (What is X?) 2) What does it mean to have a non-spaced relationship? (What is not-X). Both X, and “not X” are necessary to clearly define the scope and provide notice to others.

Such a scope-clarifying response could appear on the public patent record, and it would: 1) inform third parties about the reasonable scope of a word such as “spaced relationship”, and 2) Would prevent patentees from arguing, down the road, that a word like “spaced relationship” meant something different than it originally meant. Other suggestions appear here.

Conclusion: More Patents Challenged

The upshot is that under this new definiteness standard, more patent claims are likely to be challenged for being indefinite (under § 112) than under the earlier Federal Circuit standard. The Federal Circuit will have to work out some manageable rules now that their earlier standard has been rejected.

This could create some significant uncertainty as to the validity of many issued patents employing vague language.